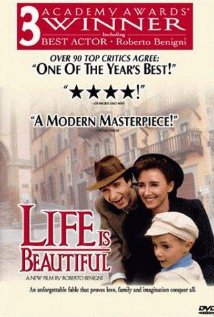

Life is Beautiful, originally titled “La vita è bella,” was released in 1997 in Italy (1999 in the United States). The movie is a drama and romantic comedy that takes place during the 1930s in Arezzo, Italy and revolves around the comedic antics and acting talent of Roberto Benigni, who plays the role of Guido, a Jewish man who arrives in town with plans to open a bookshop. The first half of the movie follows Guido as he attempts to woo Dora away from her fiancé and starts a family with her. The second half of the movie takes place in what the audience is meant to believe is a death camp, where Guido and his son Giosué are interned. During this internment, Guido deceives his son into believing their incarceration is a game, where points are awarded for good behavior and the first person to earn a thousand points will win a tank.[1]

In 1999, Life is Beautiful won three Oscars for Best Actor in a Leading Role, Best Foreign Language Film, and Best Music, Original Dramatic Score. The movie won 55 other awards and received 31 nominations.[2] But, did the movie actually earn those awards? Despite the movie having been called a modern masterpiece, there are many critics and reviewers who believe the movie doesn’t live up to the hype it received, referring to it as an “unholy film,” or a “cinematic abortion.”[3] This paper will explore and present major themes in those negative reviews, looking for common complaints that may be used to point out potential weaknesses in the movie. There are a number of criticisms of the movie among reviewers, but surprisingly, after reading approximately one-hundred reviews from IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes (which links to external sites, including Time Magazine, Salon.com, and SFGate), I discovered that almost all of the complaints fall into just a few categories, including poor acting, implausibility of the plot, historical inaccuracies, the poor choice of humor, and a general insensitivity to the victims and survivors of the Holocaust itself.

The main complaint regarding the quality of acting begins with Benigni himself, who one reviewer describes as “a six-year old trapped in the body of a middle-aged Italian man on a steady diet of Red Bull and Ecstasy.”[4] Benigni’s performance of Guido became difficult for some viewers to watch, for a few reasons. Benigni is, first of all, overly energetic throughout the movie and talks incessantly, rarely allowing any other character get a word in edgewise. This problem is also indicative of bad directing, since Benigni was both the director and lead actor. His overwhelming of the storyline through Guido leads directly to the next problem with acting in the movie: the nature of the other characters. Perhaps because they have so few lines, they have no room to develop as independent characters and remain two-dimensional, cardboard cutouts. One reviewer complained of the irony of Jews being dehumanized into a faceless mass by Life is Beautiful in much the same way they were dehumanized by the Holocaust itself. Overall, reviewers noted that all of the characters in the movie merely act as targets for Benigni’s gags or as foils to emphasize the good natured optimism of his leading character, Guido.[5]

The second largest complaint generally centers on the implausibility of the plot itself. The movie is divided into two distinct portions: the town scene, where Guido woos Dora, they get married and have kids; and the concentration camp scene, where Guido lies to his son about the nature of their surroundings in an effort to shield him from the horrors of reality and thereby preserve his innocence. Regarding the first half of the movie, most reviewers complained that Guido’s buffoon antics make him a completely unbelievable character that would not have been able to attract Dora, who would have, in the words of one reviewer, been more likely to have a restraining order issued against him. The first portion of the movie was generally described as contrived, predictable and ultimately useless in terms of lending anything useful to the second half of the movie. One reviewer summed it up quite well by saying that when the movie transitioned to the second half, he felt as though he had changed the channel on his television.[6]

In the second half of the movie, the implausibility of the plot was even more evident. Reviewers cited specific cases which make the movie impossible to believe or take seriously, starting with Guido’s intentional failure to relay important instructions to the Jews who have just arrived in the death camp, instead creating a fanciful speech about the rules of the “game” that he says is being played, for the sole benefit of his son. Had this really happened, it is entirely likely that it would have been discovered, leading to Guido’s death, either by the Nazis or by the Jews who were left in the dark about what was going on because of Guido’s disregard for their lives. Also hard to believe is that Guido is able to hide his son in a death camp after all of the other children are exterminated. And not only did Guido hide him, he had his son speaking on an intercom system to communicate with his mother in the conveniently nearby women’s camp, which did not result in the death of either the father or the son, though it should have. The biggest implausibility of all is that the kid actually believed the lies his father was telling him. Reviewers stated that the kid is depicted as being intelligent, so how could he have spent any time at all in a death camp without realizing what was going on, especially after all of the other kids disappeared?[7]

This leads directly into the next major complaint, which was the lack of historical consistency present in the movie. To start with, Guido and Dora’s marriage never could have happened, because marriages between Jews and non-Jews had been made illegal. The camp that Guido and his family are taken to is mentioned to have a crematoria and mass killings, which would make it a death camp, and yet, according to reviewers, all of the death camps were in Poland and Italian Jews remained in Italy. Most of the historical criticisms revolved around the conditions portrayed in the death camp itself. In a real death camp, people would not have appeared well-fed and well-dressed. People would not have had a bunk to themselves. Guido would not have had freedom of movement to wander the camp as he pleased. Central areas with intercom systems would not have been left unattended and had a Jew taken it upon himself to use the camp intercom without permission, he would have been killed on the spot. Had a Jew spoken to a guard, he would have been killed on the spot. Death wouldn’t have been hidden away in foggy piles of dream-like bodies; it would have been casual and ever-present. There is no way Giosué could have missed it. One reviewer wrote that the death camp looked more like a fat kids’ summer camp than a place where people were being systematically murdered. [8]

And perhaps that’s the biggest problem with the movie. The audience is led to believe that the lies being told are meant to spin a horrible situation into a fable to preserve the innocence of Guido’s son. In the beginning of the movie, the story is presented as a fable, but some reviewers didn’t feel that labelling the movie as a fable helped make it any more believable, because fables are meant to deliver a moral truth and what moral truth is there to Life is Beautiful? That lying makes life bearable? That’s certainly not what the movie is billed as delivering. The DVD box cover insists that “love, family and imagination conquer all,” but that’s not possible, or at least it’s not possible given the way the movie is portrayed, because if it were, no one would have died in the Holocaust. Certainly Guido wasn’t the only person who loved his family and had imagination. What about all of the other people? Why didn’t their humor save them? Maybe they weren’t funny enough.[9]

The type of humor used in the movie was another big issue with reviewers, including many reviewers who gave the movie moderately good ratings. Benigni’s brand of humor is very physical and includes a lot of slapstick humor, which for some was bad to start with, but for others could have been fine, had he been able to pull it off well. Many people complained that his jokes were entirely predictable and because you could see them coming, there was no reason to laugh when the moment arrived. For example, when an egg goes in a hat, it’s eventually going on someone’s head. Benigni was accused of grandstanding and trying so hard to be cute that he forgot to be funny. He was also accused of trying too hard to be Charlie Chaplain, but wound up just being loud and obnoxious. Reviewers also stated that instead of creating his own version of “The Great Dictator,” Benigni produced something much more similar to an extended episode of “Hogan’s Heroes.” He was accused of using the Holocaust as a prop to hide his poor comic ability and earn himself an Oscar, because including the Holocaust would make his movie critic-proof.[10]

That point brings us to the final, and perhaps most often cited, complaint about the movie: it is completely insensitive to the nature of the Holocaust, what it meant for the people who were victims of it, and what it should mean for those of us who learn about it today. The movie was, according to multiple reviewers, so sanitized that it probably wouldn’t even have offended the Nazis. A few reviewers said Life is Beautiful would have made great Nazi propaganda for Goebbels to show the Red Cross, to prove that life in the camps wasn’t so bad after all. Many reviewers called the movie an attempt at neo-Nazi revisionist history that denies the overwhelming horror of the Holocaust and that the movie obscures the human and historical events it set out to portray. It doesn’t expand our knowledge of the Holocaust and instead acts as a plot device to help Benigni bring more attention to himself.

The negative reviews of this movie have very strong arguments that point to serious flaws in the movie that could have been addressed to create a better movie. The movie doesn’t really show that life is beautiful. It shows that life for characters created in the author’s imagination is beautiful. If depicted realistically, this movie would not have ended well for any of the characters involved, and without those elements of realism, the movie cannot really hope to deliver a message as strong as family, love and imagination conquering all, because in the movie, that doesn’t happen. Instead, events are set up in such a way, and history is rewritten in such a way, to make it possible for “all” to be conquered. Had elements of real terror been included in the movie, alternated by more fantastical scenes as recollected by Giosué, it could have been possible to pull of what Benigni intended, but instead, he created a platform for selling himself, reducing all but the leading character to caricatures of human beings, doing implausible things in inaccurate settings using poorly thought out humor and ultimately desecrating the memory of millions of people who died in the camps.

[1] IMDb, “Plot Summary For Life is Beautiful,” 2013.

[2] IMDb, “Life is Beautiful (1997),” 2013.

[3] IMDb, “Reviews & Ratings for Life is Beautiful: La vita è bella (original title),” 2013.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

References

Flixster, Inc. 2013. “Life is Beautiful (La Vita è bella) Reviews.” Rotten Tomatoes by Flixster. March 8. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1084398-life_is_beautiful/reviews/.

IMDb. 2013. “Life is Beautiful (1997).” Internet Movie Database. June 15. Accessed June 15, 2013. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0118799/.

—. 2013. “Plot Summary for Life is Beautiful.” Internet Movie Database. June 15. Accessed June 15, 2013. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0118799/plotsummary?ref_=tt_stry_pl.

—. 2013. “Reviews & Ratings for Life Is Beautiful: La vita è bella (original title).” Internet Movie Database. June 8. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0118799/reviews?filter=chrono.