Paul D. Barclay’s “Peddling Postcards and Selling Empire: Image Making in Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule” and Leo Ching’s “Savage Construction and Civility Making: The Musha Incident and Aboriginal Representations in Colonial Taiwan” are both articles that deal with the creation and distribution of propaganda in and about Taiwan. Specifically they both focus on how the aboriginal population was represented to the outside world to suit the needs of the colonial government. Paul Barclay focuses on the use of visual imagery through commercial postcards as propaganda, produced and distributed by the colonial government to generate a specific image of the aboriginal population. Leo Ching writes about the use of stories as propaganda, both to reinforce an image of the noble untamed savage and later as an attempt to generate feelings of loyalty in the Taiwanese population. Both authors make strong cases to support arguments while also touching on deeper issues concerning modernity and colonialism itself.

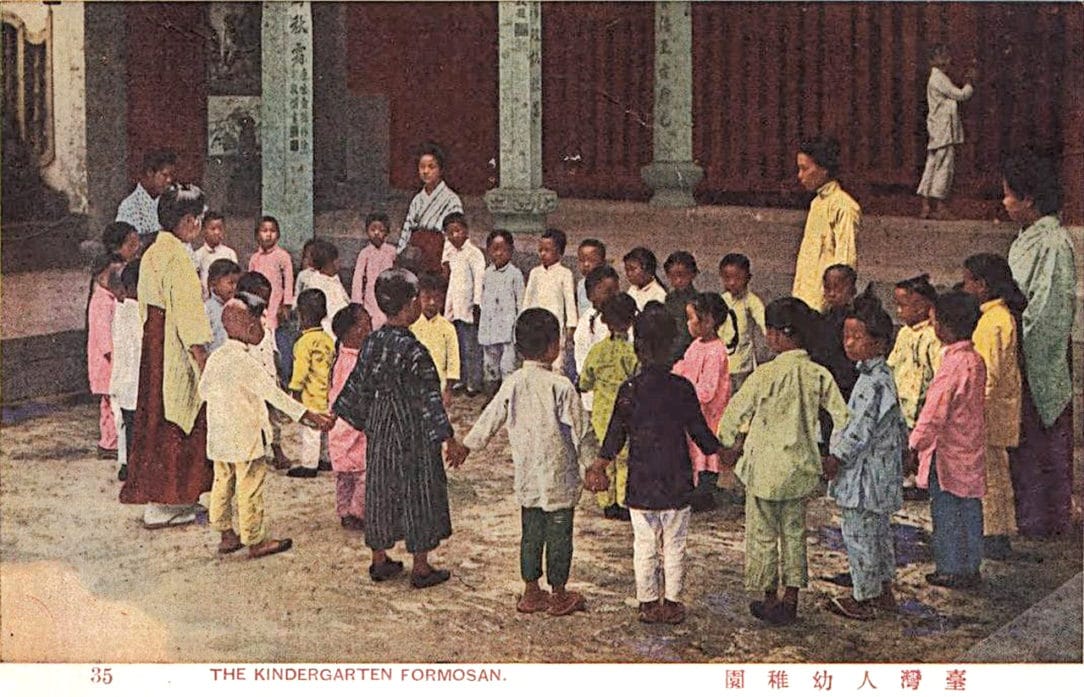

In “Peddling Postcards and Selling Empire: Image-Making in Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule,” Barclay examines the role that picture postcards played in promoting Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan. Specifically, he argues that picture postcards were used to promote a particular view of the Han Taiwanese and the aborigine Taiwanese populations that legitimated Japanese colonial rule. The vast majority of the available postcards depicted aborigine populations even though they were a small fraction of the population and depicted those aborigines as untouched by modernity, savage, and isolated. In other words, aborigines were presented to the world as the true Taiwanese and as backward, pre-modern people they were used as justification for Japan’s supposed civilizing mission.

Barclay’s main sources of primary material are postcards and personal photographs collected by US Consul Gerald Warner during his tenure in Taiwan from 1937 to 1941. Warner possessed both commercial postcards and personal snapshots that were placed together in the same collection, sometimes side-by-side. This collection was later donated to the Special Collections library at Lafayette College. The author argues that given the quantity of material provided by Warner, the collection “constitutes a body of ‘related and contextualized’ visual documents” that he believes can be used to understand the difference between reality and the official narrative of indigenous life in Taiwan.[1]

Barclay’s examination of the images in the Warner collection is broken down into three general categories: images of martial masculinity, images of “savage beauty,” and images that reinforce stereotypical beliefs about the division of labor in indigenous societies. Barclay argues that in the first two of these categories, the subjects of the photos were anonymized. The subjects were also presented in traditional or prestige garments that did not accurately depict what they actually wore on a day-to-day basis in an attempt to make them appear exotic. Warner’s personal snapshots showed a much more integrated and modern indigenous population, but images of mixed dress or use of modern items was absent from the commercial images, all of which were derived from official outlets or government sources.

The colonial government was preventing people from taking photographs of their own while handing out postcards that perpetuated the narrative of the timeless native. Why would the colonial government be interested in presenting the aborigines as timeless and pre-modern? How would images showing the successful modernization efforts of Japan’s colonial government not have served Japan’s purposes? Would it not have validated their position as bringers of civilization? The answer can perhaps be found in Leo Ching’s analysis of “The Savage,” in which Ching attempts to set the psychological backdrop for his later analysis of Japanese propaganda stories.

Like Barclay, in “Savage Construction and Civility Making: The Musha Incident and Aboriginal Representations in Colonial Taiwan,” Leo Ching analyzes media to uncover the propaganda narrative being promoted by the colonial government. Rather than examining images and postcards, Ching focuses primarily on two popular representations of aborigines from the 1910s and 1930s, “The Story of Goho” and “The Bell of Sayon.” First, however, he tries to explain the Japanese mentality towards colonialism through an analysis of “The Savage,” a story that shows the Japanese understood the inherent contradictions in using colonialism to become part of the civilized world.

The main character, Takawa, strives to become more savage because in savagery he sees an inherent nobility. He finds himself repulsed by the indigenous woman who is mimicking Japanese civility, because in her, he sees a reflection of the colonial Japanese, civilized on the outside, savage on the inside. This story helps to explain why so many Japanese visitors to aboriginal areas, like those mentioned in the travel accounts analyzed by Naoko Shimazu in “Colonial Encounters: Japanese Travel Writing on Colonial Taiwan,” found it so deeply unsettling to see the aborigines becoming assimilated into Japanese culture. Without the stereotypical savage as a counterpoint to Japanese civility, the Japanese were forced to confront the savage nature of subjugating another people. Perhaps this is why the image of a timeless savage was so popular as a postcard motif, or why it was used so prolifically by the colonial administration to maintain that distinction between Japanese and Other.

Ching argues that ‘The Story of Goho” represents the initial colonial construction of the martial savage, like those represented in the Warner collection’s pre-1930s postcards. “The Bell of Sayon” represents the tendency after the Musha (Wushe) uprising to idealize the primitive nature of the aborigines and emphasize their potential for a transformation into loyal imperial subjects. The postcards that Barclay examined show a similar trend. However, he attributes the disappearance of martial scenes and the inclusion of Japanese, but not Chinese, garments in images of indigenous peoples to official anti-Chinese paranoia. After reading Ching’s explanation of the meaning of “The Bell of Sayon,” it seems more likely that these postcards reflected the administration’s new goal of building loyalty to the empire, assimilation and eventual conscription into the military.

One point not addressed by Ching is how these stories were distributed and how well they were received. The story about Goho was produced during campaigns by the colonial government to subdue the aborigines. They were simultaneously attempting to get financial backing from local Han Taiwanese. Neither audience was likely to be receptive to a propaganda folk story produced by the Japanese. Similarly, “The Bell of Sayon” was meant to inspire loyalty to the Japanese empire. Was it successful? By what measure? Ching writes that Sayon was targeted at Japanese as well as aborigines, so was the purpose of the story more to reassure Japanese that aborigines could be trusted to serve a military purpose?

Though Barclay’s argument could have been strengthened by using more personal snapshot sources, through careful art analysis he reveals how a romanticized image of Taiwanese aborigines was created, packaged and sold. The impact of these images on world public opinion was meant to legitimize Japanese colonial rule by emphasizing the need for a civilizing mission, but he misses the mark when interpreting post-1930s postcards which are better understood in light of Leo Ching’s analysis of “The Savage.” Leo Ching’s analysis of propaganda stories reveals how the Taiwanese aborigines’ image was manipulated to reflect the changing needs of the Japanese empire, first to maintain difference in order to legitimize colonization and later to instill loyalty to bolster the empire’s military forces.

References

Barclay, Paul D. 2010. “Peddling Postcards and Selling Empire: Image-Making in Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule.” Japanese Studies 30 (1): 81-110.

Ching, Leo. 2000. “Savage Construction and Civility Making: The Musha Incident and Aboriginal Representations in Colonial Taiwan.” Positions 8 (3): 795-816.

Naoko, Shimazu. 2007. “Colonial Encounters: Japanese Travel Writing on Colonial Taiwan,” in Refracted Modernity: Visual Culture and Identity in Colonial Taiwan: 21-38.

Footnotes:

[1] Paul D. Barclay, “Peddling Postcards and Selling Empire: Image Making in Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule,” Japanese Studies 30:1 (2010): 85.